The constant barcoder

My name is Jan Pawlowski. I’m a biologist working in Switzerland and Poland. My work consists of identifying species using DNA. Each species can be characterized by a specific DNA sequence, also called a DNA barcode. Many species are difficult to identify morphologically, and DNA barcodes can help to distinguish them from similar species. DNA barcodes can be used not only to identify individual species but also to detect their presence in environmental samples of water, soil, sediment or air. They can also be used to characterize the diet of particular species, including the content of our own processed food.

Here, I’m barcoding the Aleutian trench foraminifera, together with Prof. Andy Gooday from NOC Southampton, UK. The foraminifera are unicellular organisms commonly found in marine sediments. They are characterized by granuloreticulopodia. These are a special type of filamentous extensions of the cytoplasm that allow foraminifera to feed, move, and build their external shelter, which can have an organic, agglutinated or mineralized wall. The deep-sea foraminiferal community is dominated by organic-walled or agglutinated single-chambered species, which vary in shape from spherical to ovoid or tubular. They dominate the meiofaunal size fraction, between 50 and 500 microns, but some of them can be much larger. The tubular Bathysiphon common in station 12 reached up to 12 cm in length, while the complex structures of xenophyophoreans found in Bering Sea exceeded 6 cm in diameter. These mega-sized foraminiferans are Andy’s favourite object of study, while I’m mainly working on smaller sized species.

Our most exciting discovery so far has been that of huge numbers of a tiny foraminiferal species present in the < 250 microns fraction of the sediment collected in all deepest stations of the Aleutian trench. We estimated its abundance at about 100,000 specimens per square meter. The species resembles the genus Bathyallogromia, which was described from the Weddell Sea and subsequently reported from other areas, but never in such massive abundances. Its relatively simple morphology, looking like tiny transparent spheres filled with green-brownish cytoplasm (see attached photo), do not allow us to distinguish it from other similar species. DNA barcoding will be necessary to tell whether this is just another species of Bathyallogromia or a new genus specifically adapted to hadal depths. If the later hypothesis is true, we will call it Hadallogromia, but let’s see what the DNA will tell us.

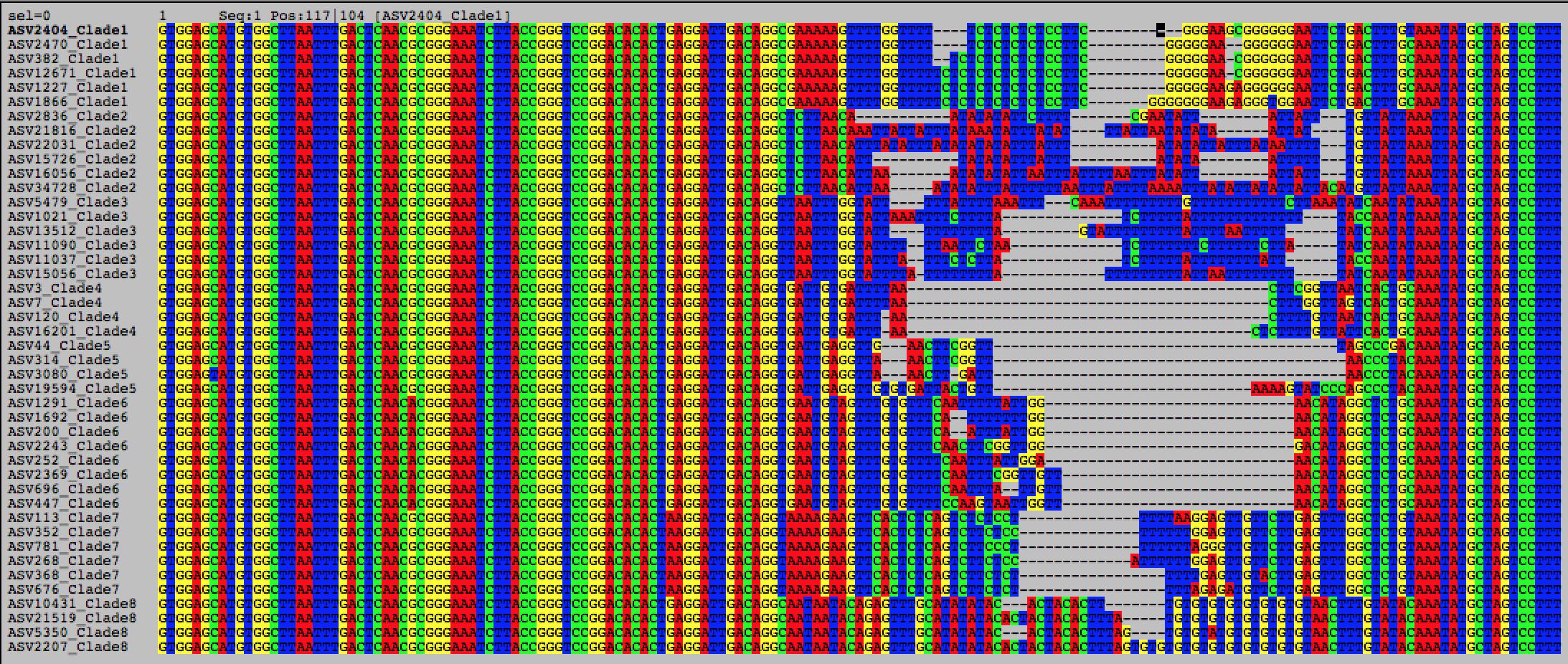

In addition to sorting specimens for DNA barcoding, we also collect sediment samples for DNA metabarcoding. This approach, based on high-throughput amplicon sequencing, allows us to survey the whole community without sorting individual specimens. It is particularly useful for exploring microbial and meiofauna diversity. In our case, the metabarcoding will allow us to detect all inconspicuous or cryptic foraminiferal species, which are difficult to isolate and identify visually. From previous studies, we know that deep-sea sediments contain huge numbers of unknown foraminiferal metabarcodes that cannot be assign to any known species. We can reduce this gap by barcoding and describing a few isolated specimens, but the challenge to create a complete reference database of deep-sea foraminifera is insurmountable, given the vast extent and largeness of the oceanic floor. Therefore, metabarcoding provides an important complementary insight into diversity patterns that cannot be assessed using traditional methods.

DNA barcoding and metabarcoding are two faces of the same effort to describe the unknown diversity of deep-sea realm, and this is what makes the biggest passion of my life.

Jan Pawlowski