Life at the bottom of the sea – a brief story about small isopods and other critters

Hello from the other side of the world! My name is Henry Knauber and I am a PhD student in deep-sea biology at the Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt. For my PhD thesis, I am investigating the extent to which factors such as depth, distance and large bathymetric barriers – deep-sea trenches and ridges, for example – influence the emergence of new species that populate the deep-sea floor.

To investigate this question, I work with isopods, which are only a few mm in size. Although isopods can be found almost everywhere (even out of the water in our basements and under dead wood!), they live mainly in the deep sea and show an enormous diversity of lifestyles there: some wander across the seabed, while others move around by digging or even swimming! There are also many highly specialized isopods that live as parasites on other crustaceans or fish. What all isopods have in common is the fact that they breed and carry their offspring around in a brood pouch called a marsupium – just like a kangaroo!

To find out even more about these whimsical critters, I am on board RV “SONNE” as part of the AleutBio expedition. Together with a team of international scientists, we are investigating the biodiversity at the bottom of the seas in the Aleutian Trench and the neighboring Bering Sea – the “gateway to the Arctic”. To do this, we use a variety of different instruments that have the most curious nicknames on board. There is talk of things like MUC, OFOS, AGT and EBS. I’d like to tell you a little about the last one, the EBS – or its full name, the epibenthic sledge – which is a huge, metal sledge in the shape of a box, equipped with two very fine-meshed nets, pulled over the deep-sea floor to catch the sediments and the tiny organisms called macrofauna. While the EBS is doing its work at depth, for the EBS team it means waiting for our sled to return to the surface – a process that can take as long as 10 hours at hadal stations beyond 6,000 meters. When the EBS returns to the deck, intact and with samples, things have to move fast! The sediment is sieved and filtered to find the animals in it, which are then fixed in alcohol and stored in a cool place for future molecular analysis.

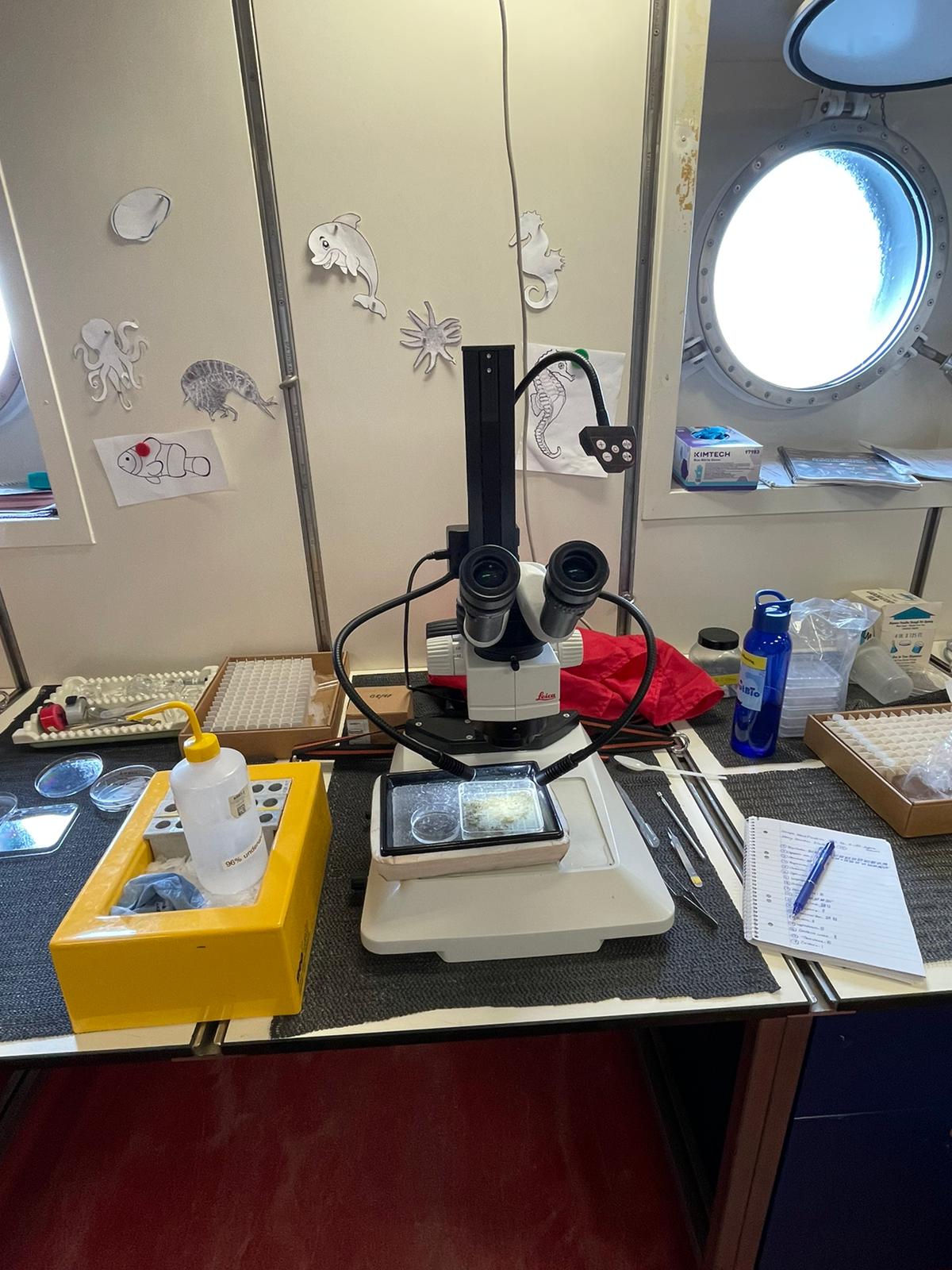

During the “live sorting”, we pick out some of the fresh animals from the sediment before preservation, and immediately set about identifying them taxonomically using the microscopes, so that we get an initial impression of what lives on the seabed at this station. There are all kinds of things to discover here! From small sea stars and brittle stars as well as roundworms and bristle worms to sea urchins and sea cucumbers to the most diverse crustaceans such as amphipods, seed shrimps, comma shrimps and of course isopods, everything is there! Life on board a research vessel may not always be easy, for example when you have to get out of bed in the middle of the night to process your samples, but getting to see creatures that live many kilometers below us, in a world that is almost completely unknown to humans, makes up for any strain and makes the scientist’s heart beat faster!

That’s enough from me for now – I will now go back to the lab and search sediment samples for animals!

Best regards from the open North Pacific!

Henry Knauber